Shopdropping :: Three Case Studies

by Marisa Jahn

Shopdropping, also known as reverse shoplifting, is a tactic that relies on the insertion of art into public places of commerce. You’ve probably heard of a few examples: the Barbie Liberation Organization, who swapped voiceboxes of 300 Barbies and G.I. Joes, groups such as Minerva Cuerva’s Mejor Vida Corporation who produce barcode stickers that when scanned ring up cheap items (intended to be placed onto more expensive items), various artists and activists ‘gifting’ conglomerate stores with their own personal items, etc.. I’m guessing that alongside and simultaneous with the rise of consumer culture is a parallel and unsung history of shopdropping. In its contemporary incarnation, shopdropping ranges from traditional commodity critique to complex strategies that detourne situations, present alternatives to normative systems of exchange, and graft together alternate economic regimes. The three case studies below explore these different trajectories within the art of shopdropping.

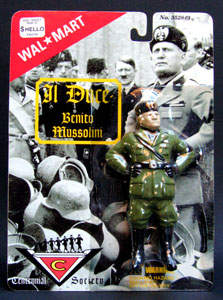

A prevalent example of shopdropping is the introduction of ‘alien’ or extrinsic items into the language or space of commerce. In 2000, Packard Jennings fabricated an action-figure doll bearing resemblance to the 20th century fascist leader Benito Mussolini, colloquially referred to as ‘Il Duce.’ The Mussolini action figure was inserted into Wal-Mart and repurchased by the artist while a spycam video-documented the ensuing comical conundrum (confused workers assigning a value to the item, the manual entry of the word ‘Mussolini’ onto the receipt, etc.). The success of Jenning’s project lies in its ability to elbow its way through the apparatus of mainstream capitalism, forcing the store recognize and come to terms with his item’s otherness, its alterity.

While Jennings’ project does not bear any significant economic consequence (other than the amount that Jennings contributed to Wal-Mart for the purchase of his action figure.), other projects incorporate the economic transaction into the piece itself. In a series of work entitled Shopdropping (2003), Zoe Sheehan bought a woman’s blouse from a Wal-Mart located in Berlin, Vermont, and proceeded to duplicate the item by hand. Sheehan copied its pattern, using matching fabric, thread, and embellishments (such as lace, elastic, ribbon, embroidery, and fabric paint) to make as faithful a reproduction as possible. After re-attaching the original tags, including the price tag, the simulacrum was then returned and presumably sold for the original’s price of $9.94. With an artist’s signature conspicuously absent, we are left to assume Sheehan’s craftwork was sold to unwitting shoppers, a silent comparison between hand-made and mass-produced labor.

Sheehan’s project then becomes more elaborate: the original Wal-Mart shirt was then displayed in a gallery setting and given a value commensurate with commercial art prices. Sheehan describes this displacement of objects in different economic registers as “a black hole of value that shifts the economic burden [of her labor] onto those who can afford it. . .” In other words, in asking the art audience to absorb the costs of her materials and labor, the artist asks the collector to vicariously partake in the one-way spiritual intimacy with the imagined shopper wearing her hand-made underwear. Sheehan also asks the collector to participate in an act of faith—faith that the mass-produced Wal-Mart version displayed in the gallery is of value because of its transcendental relationship with the artist-made version. By asking the collector to suspend his/her traditional interest in ‘investing’ in the artist’s craft, Sheehan’s project ultimately obviates the concern over authenticity and presents the simulacrum as a more relevant discourse.

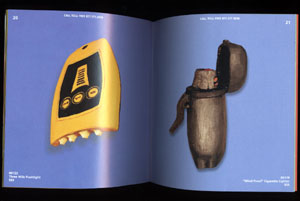

While Sheehan’s nameless and faceless hand-crafted objects are recirculated into the economy without the shopper’s awareness of this invisible labor, other projects foreground the role of labor involved in commodity production and consumption. Conrad Bakker’s consummately deadpan Untitled Projects is a series of wooden objects carved and painted to resemble functioning technology (radar detectors, binoculars, lighters, flashlights). The objects bear traces of their production: visible chisel marks, brush strokes from the oil paint, and imperfections indicate the obejcts’ inability to function as anything other than sculptures. Bakker then assigned the sculptures an ISBN number and marketed them through a glossy mail-order catalogue at prices comparable to the products they resemble. Shoppers calling the catalogue’s 1-800 number found themselves in intimate conversation with the artist, who took orders, shipped items, and produced more on demand, a process which often took considerable time. Bakker describes his construction of an intentionally inefficient system when compared to the hallmark efficiency of capitalism: “I was interested in slowing down and making strange the networked transactions (the economic space) so that as the objects moved along the path from producer to consumer, they generated a specific set of intentions (spaces) where the process could be critically examined.” By emphasizing the relationships built between shopper and artist, Bakker presents an alternate economic model—a hybrid between a gift economy and commodity-based culture.

Jennings, Sheehan, and Bakker thus present three different models for the relationship between the art object and economic regimes. While parodying the histrionic language of action figures, Il Duce Action Figure constructs its own code, then inserted into the economy to confront the apparatus of hegemonic capitalism with its alterity. In Sheehan’s Shopdopping, a poetic silence is constructed from the secret we share as an informed audience; asked to pay the price of market-rate legitimated art, we (the art audience) are then asked to assume the economic burden of this privilege/secret. While Sheehan’s work works within (and ultimately reifies) the disparity between two different cultural registers (Wal-Mart shoppers vs. art audience), Bakker’s project presents an alternate economic model based on the valorization and recognition of labor.

From March 11-April 10, 2005, Packard Jennings’ work will be featured in an exhibition entitled Shopdropping: Experiments in the Aisle curated by Pond, a non-profit art organization dedicated to experimental public art. Co-founded by artist, writer, educator, and curator Marisa Jahn, Pond is currently engaged with various projects including Invisible 5, an experimental audio tour of the hidden toxic landscape along California’s I-5 highway (by artists Amy Balkin, Kim Stringfellow, Tim Halbur, Greenaction, and Pond); OneTrees, an ongoing city-wide project originated by Natalie Jeremijenko involving the planting of pairs of genetically identical trees throughout the Bay Area’s diverse microclimates; and more. Visit Pond at www.mucketymuck.org or www.marisajahn.com.