Tower as Tableau:

A Proposal for Kennedy Plaza

by Tim Waterman

On ‘vitality’: This project is predicated on the hunch that radical, critical interventions in the city might also backhandedly serve an ameliorative function: that while subverting, appropriating and repositioning, or negating the perceived and conceived urban order, a critical gesture might fly under the radar to be rationalized not as critical but as nice. A mischievous act of détournement is digested, a grain of sand that forms a pearl.

It was important that this project be neither interactive nor didactic. The city as a whole is incomprehensible, and the quality of the resultant alienation is all too often now compromised by instructional signage and participatory installations. These arrogantly propose a coherence to the city, a grand plan and an illusion of legibility. The city itself does not allow such a packaged image, so these efforts towards instruction and participation are trivialized and with them the very values that they try to advance. It may well be that the average citizen knows this intuitively, as the superficiality of such gestures seems to speak little to everyday urban experience. Of course, the city is shaped by human industry and a multi-dimensional concatenation of human information, but the city has its own intentions and opacities. We may build and maintain, like the farmer who plants and shears the hedgerows, but inside the leaves and branches, the rooms and alleyways, thousands of actions are constantly reshaping it from the inside in patterns and for reasons that defy understanding.

This project grew from the idea that the city might dream of itself—its spaces, flows, and inhabitations—and that if it did so, those dreams might suggest ways in which forms might be thrown up, carved in, or stretched through or across the space of the city. In analyzing Kennedy Plaza, it was striking that due to the multiple changes to the space over time, every axis had been compromised to the point that no buildings in the square could be experienced frontally despite their monumental ambitions and the importance of their political and social functions (City Hall, the Federal Building, the Post Office). The tallest buildings in Providence are also arrayed only along one edge of the square, creating a peculiar one-sidedness of the type that may be observed on New York’s Fifth Avenue or along Edinburgh’s Princes Street. If the city were to autonomously generate form in answer to this, I reasoned, it would strive for frontality and it would seek to balance the visual mass of the buildings along its ‘heavy’ side.

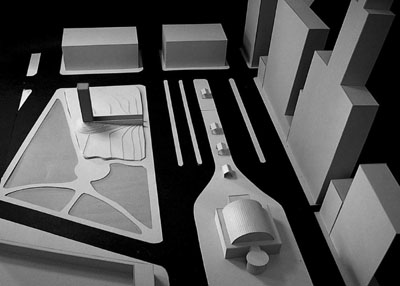

To evoke the idea of the form ‘thrust up’ by the city, the formal response took the form of a tower, 120 feet tall and 20 feet square in plan. This form would be mirrored by a cut of the exact dimensions of the tower, symbolizing the amount of matter displaced from the ground in the ejection/erection of the tower. Further, emanating from the dream life of the city, this form would be, in a sense, self-referential and enigmatic, belying the visual logic of its monumentality. Thus it would unabashedly inhabit the realm of the sublime.

Early explorations had necessitated collages which voided the plaza of its content, originally as an aid to understanding simple relationships between the vertical and horizontal planes. These collages, however, suggested such a subtractive move rather than additive effects would be beneficial to the activation or charging of the space. The tower’s frontality was thus to create a tableau, which in the words of Roland Barthes (paraphrasing Diderot), “ . . . is a pure cut-out segment with clearly defined edges, irreversible and incorruptible; everything that surrounds it is banished into nothingness, remains unnamed . . .” (Barthes 1977, p. 70). The act of ‘cutting out’ the tableau can be likened to asyndeton or ellipsis, (where connecting words within a phrase are omitted, which often implies further, unnoted possibilities). In other words, it is a subtraction that suggests an addition. The tableau, transposed into the city, thus simultaneously absences and presences, voids and fills. Michel de Certeau finds asyndeton within the speech act of walking: “. . . in walking it selects and fragments the space traversed; it skips over links and whole parts that it omits. From this point of view, every walk constantly leaps, or skips like a child, hopping on one foot. It practices the ellipsis of conjunctive loci (emphasis mine).” (Certeau 1974, p. 101) These “figures of pedestrian rhetoric” (Certeau 1974, p. 102) that are constructed by the individual do not ‘make sense’ of the city, but rather accompany and direct trajectories: they provide shifting frameworks for meaning and understanding that are simultaneously transcendent, imaginary, pragmatic, and quotidian.

Barthes speaks of the tableau in painterly terms, which aids in drawing parallels between its asyndeton and that of the pedestrian speech act: “Necessarily total, this instant will be artificial . . . , a hieroglyph in which can be read at a single glance . . . the present, the past and the future . . .” (Barthes 1977, p. 73) The tableau created by the tower, however, is otherwise directed. Its enigmatic monumentality is a work of voiding: it is in itself a void. The tower was initially intended to contain a room, a 20-foot cube at its top, accessed by an elevator, but perhaps the tower requires neither entry nor enclosure. This might, in fact, compromise the tableau and the uneasy opposition that is required to activate its effect. Thoroughly direct and un-subtle, it is intended to create such a strong subtractive effect that it would repulse the viewers sending them back into the city, more firmly grounding them as the loaded gun provokes the desire to live or the proximity of the precipice reminds one to resist the temptation of the edge.

References

Barthes, Roland. 1977. “Diderot, Brecht, Eisenstein” in Image,

Music, Text, trans. by

Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang.

Certeau, Michel de. 1974. The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. by Steven

Rendall.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Tim Waterman is completing his Master's thesis in landscape architecture and

urbanism at the Rhode Island School of Design. He is a poet, an author, a

visual and performance artist, a love, a dreamer, a raconteur, a provocateur,

and a roustabout.